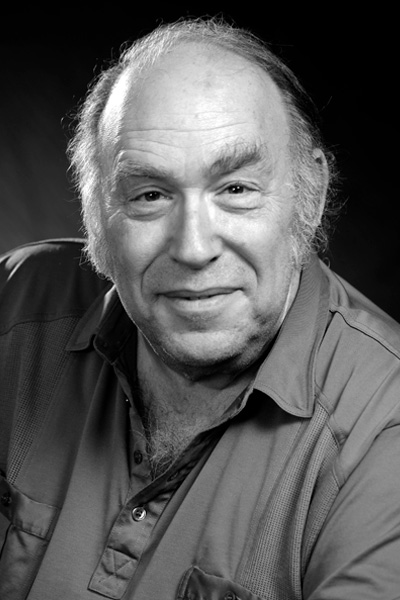

Our Writers of the Future Writer’s Dad: Helping Writers Become Authors

“It’s a given that when you’ve had a successful career, you pay back. But in this field, it’s almost impossible because, by the time you’ve been a remarkable success, everybody who helped you is either rich, or dead or both. So you pay forward.” —Mike Resnick, 2018

And Mike Resnick demonstrated just how seriously he took this philosophy to heart in how he operated as a writer, editor, and friend to so many.

I was introduced to Mike by Kevin J. Anderson who recommended him as a Contest judge. This was back in August 2009 with just enough time to invite him to attend that year’s awards ceremony, which back then was held in the fall.

Mike agreed and so became a Writers of the Future Writing Contest judge in 2009. In subsequent years, he proved himself a willing mentor to each new group of winners, many of whom became “Mike’s Writers Children.”

Two years later, Mike stated in an email, “I’ve been ‘adopting’ a beginner or two almost every year since about 1990. I collaborate with them, get them into print, vet their early stories before they submit them, and recommend markets to them (and them to editors). I imagine I’ll choose one or two each year I’m a judge; it’s my way of paying the field back, so you can understand how pleased I am to be working with an organization devoted to that cause.”

That same year he provided an article for L. Ron Hubbard Presents Writers of the Future Volume 27 entitled, “Making It.” In it, he shared what he saw a commonality amongst writers. First, a love of writing. Second, a constant study of the field. Third, talent. And fourth, perhaps the most essential quality which he defined as a fire in the belly. (You can read the article in its entirety at the end of this post.) Over the course of our relationship, he personally took twenty-five winners under his wing to publish while co-authoring novels with fourteen winners.

In 2013, Mike sent an email announcing that he was editing a new magazine called “Galaxy’s Edge” while proudly listing eleven finalists from the Contest he would be publishing in the first five issues, as well as the three finalists in his Stellar Guild line of books. He ended his email, “So I’ve found a bunch of talent here, and I hope you’ll keep asking me back. I pledge to continue doing my best for them.”

In 2017, while accepting the L. Ron Hubbard Lifetime Achievement Award, he stated that since the 1990s he had done everything he could to help “Mike’s Writer Children” and how proud he was of what he had written—but these books were in the past. He was expecting to be proud of numerous books under contract which for all practical purposes, are the present. He closed his acceptance speech, “And this is the Writers of the Future. By definition, they should be less concerned with the past and the present than they are with other things. And because of that, I, on behalf of my writer children, and I hope 20 years from now, their writer children, proudly accept the Writers of the Future Lifetime Achievement Award.”

I already miss Mike but his legacy lives on through his writer children who now pay forward helping writers become authors.

—John Goodwin, President Galaxy Press

Making It

by Mike Resnick

Writers of the Future has been turning out writers—by which I mean successful, best-selling, award-winning writers—for over a quarter of a century now. They’ve done it long enough and frequently enough that there’s no longer any doubt that this program is not a fluke, that they really do know how to pick and train talent.

So let’s examine it from the other side. Yes, they know their stuff. They build writers. But can they build you into one?

That leads to a plethora of questions. How do you make it as a writer? Do you start with short stories and build a reputation (and can you build one in these days of only a tiny handful of print magazines)? Do you start in an easier field (and is there any easy field)? Do you begin with novels? Nonfiction? Do you attend workshops and conventions, and start networking with other writers, or are they wastes of that rarest of a writer’s commodities: time?

My answer isn’t likely to thrill anyone, because what I’m going to do is quote Rudyard Kipling: There are nine and sixty ways, of constructing tribal lays, and each and every one of them is right.

Well, I’ll qualify it to this extent: every approach is right for those who have proved it is right for them.

Eric Flint, a Writers of the Future winner, didn’t start writing until his late 40s. Within two years he was living on the best-seller list, where you can still find him. Kevin J. Anderson, a long-time lecturer and judge at Writers of the Future, made the best-seller list originally by writing some outstanding Star Wars books, but he took that enormous audience with him and has been a best-seller ever since. Patrick Rothfuss won the contest and found himself on the Hugo ballot and the best-seller list half a dozen years later with The Name of the Wind. Tim Powers and I, lecturers and judges here, don’t live on the best-seller list—but we were the 2011 and 2012 Worldcon Guests of Honor.

People and careers differ. I sold my first article at the age of fifteen, my first story at seventeen, my first novel at twenty. I had all the mechanical skills, but I lacked the maturity and ambition to apply myself and write anything award-worthy or even memorable, and it was another eighteen years and a couple of hundred forgettable books written under pseudonyms before I moved over to science fiction and wrote anything of value, anything I was anxious to sign my name to. That was a few best-sellers and more than 100 awards and nominations ago, which just shows that we don’t all develop at the same pace or in the same way.

And that holds for the Writers of the Future winners and finalists too. Look down the list at Nina Kiriki Hoffman, and Nick DiChario, and Dave Wolverton, and Karen Joy Fowler, and Robert Reed, and Jay Lake, and Tobias S. Buckell, and Stephen Baxter, and Amy Sterling Casil, and K. D. Wentworth, and R. Garcia y Robertson, and Dean Wesley Smith and all the others. Each got to where he or she is by a different route, some faster than others.

But they have certain things in common. We all do.

First, there’s a love of writing. A lot of writers hate writing and love having written. Not the ones who make it. They love words, they love pushing nouns up against verbs and seeing the results, they love creating their very own worlds and then inviting you into them.

Second, there’s the constant study of the field. There are certain categories of fiction that require almost no preparation. Others, like the detective story, ask you to create a hero and then run him through his paces book after book after book. Not science fiction. With all time and space at the author’s disposal, about the only thing he can’t do is tell the same story over and over. He can experiment, he can innovate, he can and must create; what he cannot do is repeat, not only himself but what has gone before, which is why he must be well-read in the field and stay abreast of what’s going on.

Third, there’s talent, and the ability to get the reader emotionally involved with the characters and the stories. The successful author must make the reader (I’ll write it in caps so no one can miss it) FEEL, must make him love or hate or fear or laugh, or, in short, react. If he makes him think, as our progenitors Hugo Gernsback (creator of the field) and John Campell (the first great editor) believed was science fiction’s mission, so much the better and the author has written a better story for it. But if the reader can’t respond emotionally, then the author has written a fictionalized polemic or scientific cross-word puzzle.

And there’s one more essential quality, which I will define as a fire in the belly, by which I mean an unwillingness to get discouraged or accept rejection. (A beginner asked me recently if I still get rejected. The answer was yes, every year or two it still happens. She then asked me my reaction. I said it hadn’t changed in half a century. It was, spoken so softly only I can hear it: “To hell with you, fella [or lady]. I’m taking it to your competitor, he’ll buy it, and when it wins the Hugo or the Nebula or sells to Hollywood I’ll get richer and more famous, so will my editor, and you, pal, are going to be standing on the unemployment line when word gets out.”)

Has it ever happened? I did win an award with a rejected story some years back. I don’t think anyone ever got fired for rejecting me. But the point is that you—like every writer I named—have to believe in yourself more than you believe in an editor whose tastes and priorities are different. (By the same token, never look at a story and say, “Oh, there’s no sense sending this one to Editor A. It’s just not his kind of story.” Maybe it isn’t, but it’s not your function to do his job for him. Let him decide whether or not to buy it—and remember: he can’t buy what he never sees.)

Is there more?

Sure. In this business, there’s always more.

I mentioned networking before. The writer with the hunger in the belly gets involved in that early on. He exchanges market information with his peers—and most anthologies are by invitation only, which means he finds out who the editors are and makes sure they know who he is. He learns of new markets, and in this day of the Internet, they change almost weekly. True, there are only four print magazines, where in 1954 there were fifty-six . . . but as I write these words (and it’s likely to change by the weekend) there are eighteen electronic science fiction magazines paying what SFWA—the Science Fiction Writers of America—considers to be a professional rate. And if you don’t network, you don’t learn about them. You network to find out which conventions you should go to, which ones have the editors you want to meet and the writers you want to befriend.

From the outside it may seem like the publishing world is imploding, as bookstore chains are in big trouble, and publishers are losing more writers every month to the Internet, where they have discovered that 70% is a nicer royalty rate than 6% or 10%. But from the inside, there have rarely been so many opportunities. There’s traditional publishing, of course. And there are more small and medium presses every year, a handful of which pay rates comparable to the New York houses. And there’s self-publishing on the web. And there’s podcasting. And there’s suddenly tons of money to be made in audio sales. And as quickly as the writer learns what he has to know about all these outlets, of course there will be more. And there’ll be improvements and innovations on what we have right now: e-books with animated covers and background music and hypertext, video podcasts and more.

Who will take advantage of all these opportunities? The same writers who have those four traits I mentioned before: a love of writing, a passionate interest in the field, talent and (perhaps most important, as I’ve seen many talented beginners just fade away) that blazing fire in the belly.

The Writers of the Future contestants in this book have all had ample opportunity to get down on themselves, to give up and walk away. Not one of them has quit. Every one of them loves writing, constantly studies the field they’re writing in, has enough talent to appear in this book and has that fire in the belly that all but guarantees this is far from the last you’re going to hear from each of them.

This article by Mike Resnick was originally published in Writers of the Future Volume 27.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!